Senior Colonel Zhou Bo (ret) is a senior fellow at the Centre for International Security and Strategy at Tsinghua University and a China Forum expert

One year has passed since a deadly brawl between Chinese and Indian troops in the Galwan Valley in the China-Indian border areas, which resulted in the death of 20 Indian soldiers and four Chinese troops. The aftermath is still being felt today.

Beijing was given the cold shoulder when it offered to help pandemic-devastated India. Such resentment speaks volumes of the frosty relationship, which was described by Indian Minister of External Affairs S. Jaishankar as “profoundly disturbed”.

In a few meetings with Indian scholars, I was surprised to learn how they almost invariably believed that the Galwan clash was the result of a planned attack by China. This is impossible. If China has to compete in an America-initiated great power competition, why would it suddenly divert its attention and strength away from that to take on India?

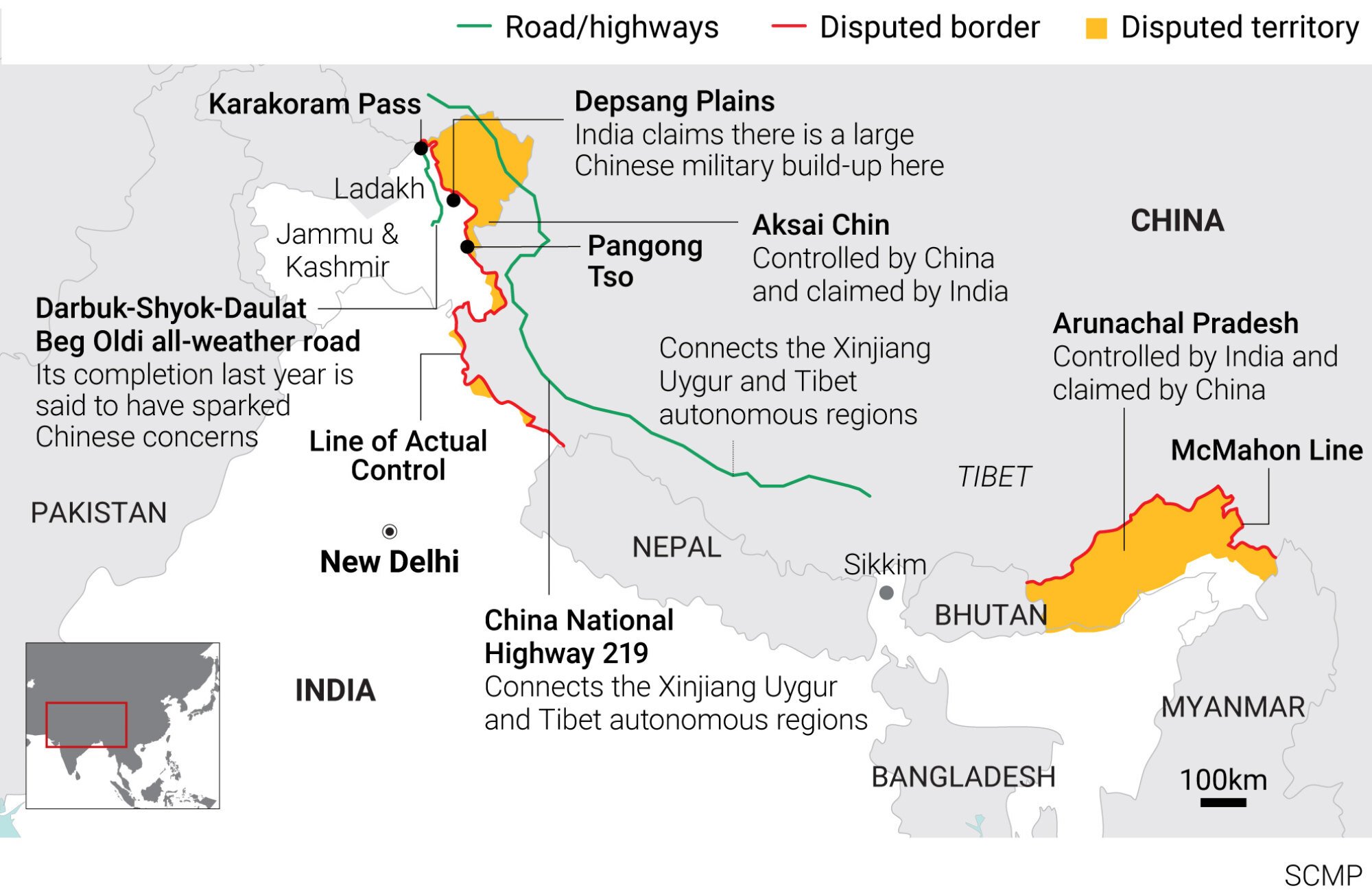

Since the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the border areas is not demarcated, it is not rare for face-offs between Chinese and Indian troops. According to the Chinese, Indian troops started to unilaterally build roads and bridges in the valley in April 2020, despite Chinese protests.

The deadly incident was dreadful in that it came closest to breaking a decades-old tacit agreement between the two countries not to use force. “In the last 40 years, not a single bullet has been fired because of [the border dispute],” Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said in 2017. But the Galwan clash, even though no bullet was fired, has changed the whole atmosphere.

The complexity of the China-India border dispute is daunting. Even the length of the border is not necessarily agreed on. China believes it is 2,000km long, while India believes it is 3,488km. According to New Delhi, Pakistan illegally ceded 5,180 sq km of Indian territory in Pakistan-controlled Kashmir to China in 1963. Both China and India maintained that the valley is their own territory.

To makes things worse, the LAC is not verified. A 1993 agreement between the two governments stipulates that “when necessary, the two sides jointly check and determine the segments of the Line of Actual Control where they have different views as to its alignment”. But when is it necessary?

The approaches of China and India seem irreconcilable. China prefers a top-down approach, which is basically a land swap based on mutual accommodation, while India insists on a bottom-up approach of verifying the LAC as the priority.

Beijing suspects that, once the alignment of the LAC is verified, India would take it as a de facto border and refuse further negotiations. Such suspicion is not entirely groundless. India has refused any talks on the position of Arunachal Pradesh, which China holds as part of southern Tibet, citing the reason that Tawang is the birthplace of the 6th Dalai Lama.

How to prevent the dispute from spilling over into a conflict? The way forward is to look back. Between 1993 and 2013, China and India reached four agreements on confidence-building measures at governmental and military levels. This is more than any bilateral agreements China has signed with other countries.

And they are substantive, too, which is impressive. Both reaffirm that they shall reduce or limit their respective military forces along the LAC to minimum levels; major categories of armaments such as combat tanks, infantry combat vehicles, large-calibre guns, surface-to-surface missiles and surface-to-air missiles are to be reduced; large-scale military exercises involving more than one division in the proximity of the LAC shall be avoided; and combat aircraft should not fly within 10km of the LAC.

If only these measures were being implemented. In fact, both sides are strengthening their military presence in the region. This is no surprise in the wake of a crisis. But when the situation cools down, both countries will have to think about how they can best make the border areas peaceful and tranquil.

One way is to resume the joint working group and ask the diplomatic and military experts working under it to find the low-hanging fruits in the confidence-building agreements. New confidence-building measures could also be ushered in. In the wake of the incident, at least 11 rounds of corps-commander-level talks were held, which helped to de-escalate the situation. Such regular meetings of front-line senior military officers should be maintained.

Both sides should also consider establishing hotlines for real-time communication. China has military hotlines with Russia, the United States, South Korea and Vietnam. Reportedly, China and Japan are considering establishing one as well. India often uses its hotline with Pakistan. There is no reason the two immediate neighbours with territorial disputes should not have similar instruments.

Perhaps the boldest step might be to establish buffer zones in the most dangerous areas along the LAC. Without prejudicing their respective positions on the boundary question, this is the most effective way to disengage and prevent conflict. Both sides agree they shall not follow or tail patrols of the other side in areas where there is no common understanding of the LAC.

Building buffer zones is a step further. And it is possible, too. From the mountains around Pangong Lake, a de facto buffer zone has already been established after the mutual withdrawal of troops.

It is ridiculous if, in the 21st century, Beijing and New Delhi are still hijacked by a dispute that is a colonial remnant, not least because apart from this dispute, they have no outstanding problems with each other.

Gone are the days when India said “Hindi Chini bhai bhai”, which means, in Hindi, “Indians and Chinese are brothers”. But China and India have every reason not to become foes. The border issue should not be a perennial curse. The two nuclear neighbours can ill-afford even a conventional war.