Senior Colonel Zhou Bo (ret) is a senior fellow of the Centre for International Security and Strategy at Tsinghua University and a China Forum expert

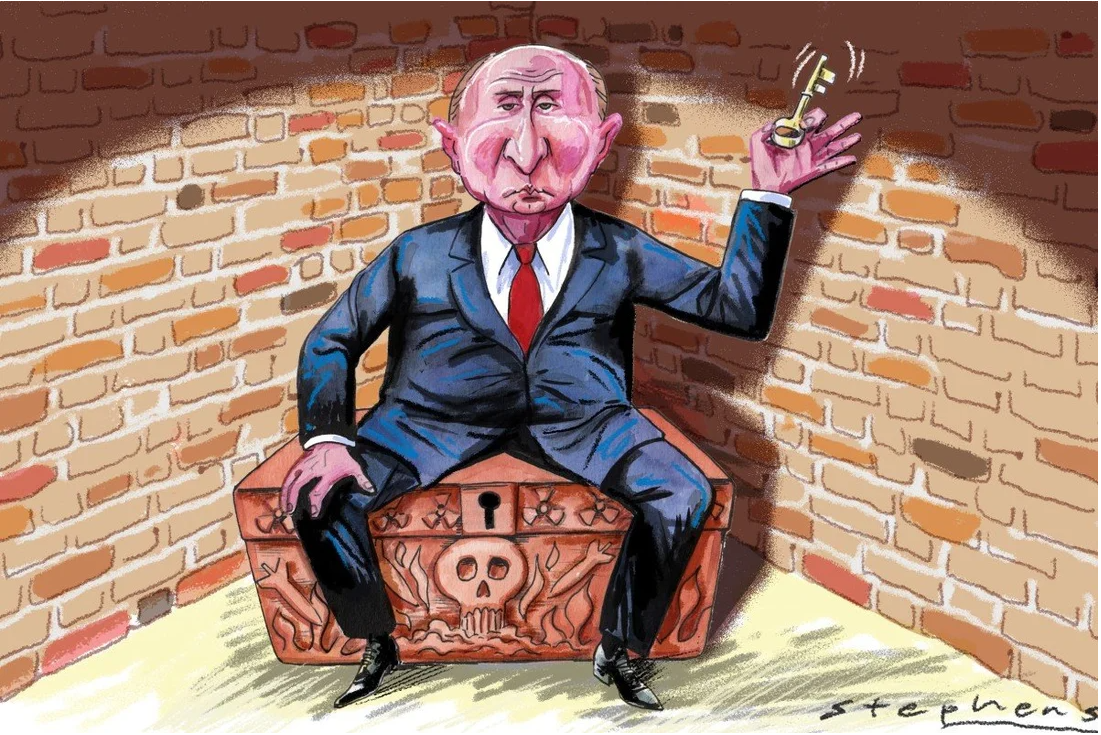

Russia is repeatedly dropping escalatory hints about possibly using nuclear weapons. It might be bluffing, but what if it is not? Unlike the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that sealed the surrender of Japan in World War II, if Russia opens another nuclear Pandora’s box, everyone can imagine the rest.

Put yourself in Russian President Vladimir Putin’s shoes for a moment. You are convinced this is a proxy war between the United States, its Western allies and Russian forces in Ukraine. Military weaponry of all sorts from Europe is pouring into Ukraine. US intelligence support reportedly helped lead to the sinking of the Moskva – the flagship of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet – and the battlefield deaths of several Russian generals.

Unlike US president John F. Kennedy, who was bold yet careful enough to reach agreement with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev on removing Soviet missiles from Cuba in exchange for the US promising not to invade Cuba in 1962, current US President Joe Biden has been provocative. He has called Putin a war criminal and said “this man cannot remain in power”.

We are closer to a nuclear war now than we were during the Cold War. No one can tell when or where Putin might use nuclear weapons. But if he feels he must rely on nuclear weapons as a game-changer in a grinding war in which Russian troops have so far fought poorly, the likelihood he will use them will continue to simply grow.

As Stephen Walt of Harvard University wrote in Foreign Policy this month, Putin has a track record of following through on his warnings. This is seen in Russia’s war in Georgia in 2008, its annexation of Crimea in 2014 and, of course, the current conflict in Ukraine.

If Putin believes he is chosen to be St George who slew the dragon – a symbol that is part of Russia’s coat of arms – the weapon he will use is not a long spear but a nuclear missile, of which Russia has more than anyone. The targets might be one or two European countries rather than Ukraine, which, home to what Putin called “one people”, is also close to Russia.

With no prospect of even a ceasefire in sight, the challenge is how to reduce tensions. As a first step, Nato could unilaterally pledge not to be the first to use nuclear weapons against Russia in any circumstances. It is unlikely that Russia will reciprocate now, but this would be a goodwill gesture and talks could start from there.

Nato can afford to make such an offer as it would not compromise its deterrent capabilities. It is hard to imagine why the 30-member transatlantic alliance with unmatched conventional forces would need to use nuclear weapons first against one adversary.

According to the Pentagon, the US “would only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners”. This is already close to a “no first use” policy.

As a second step, Nato could pledge to halt any further expansion in exchange for a Russian promise not to use nuclear weapons first. Moscow might find this proposal worth considering since its stated primary concern has been Nato’s eastward expansion.

The alliance – which could grow to 32 members if Finland and Sweden join – is already a juggernaut. All military alliances are like leeches that live on “threats”. However, if Nato has to expand because of the threat from a single nation, that says more about its incompetence than its strength.

Nato could easily argue it is not that it wants to expand but that countries fearful of Russia want to join. There is some truth to that, but it is still not justifiable. The more popular Nato becomes, the more insecure Europe will be.

Take Finland’s application for Nato membership, for example. Finnish President Sauli Niinisto told Putin how Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had altered the security environment for Finland, but the security environment is not security itself.

Does Finland have to break with eight decades of neutrality that has created a stable and pragmatic relationship between Moscow and Helsinki? This move would more than double the length of the alliance’s border with Russia and risk adding to Moscow’s feelings of insecurity.

The third step is to negotiate new security arrangements in Europe, including but not limited to a security guarantee for Ukraine. This might include a pledge not to deploy nuclear weapons in Russia’s periphery, which Moscow sees as its sphere of influence, but the key is to negotiate a new conventional armed forces treaty.

The Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty, signed in 1990, eliminated the Soviet Union’s quantitative advantage in conventional weapons in Europe. It set equal limits on the number of tanks, armoured combat vehicles, heavy artillery, combat aircraft and attack helicopters that Nato and the Warsaw Pact could deploy between the Atlantic Ocean and the Ural Mountains.

The new treaty should set a limit on Nato’s quantitative advantage in conventional weapons in Europe given the apparent disparity between Russia and Nato today. As a condition, Nato could ask Russia to reduce its nuclear stockpile, which is bigger than that of the US, France and Britain combined.

The war in Ukraine stems from Nato’s neglect of Russia’s warnings against its expansion. If Nato also neglects Russia’s warnings that it could use nuclear weapons, a nuclear war that leads to a global disaster the world managed to avoid during the Cold War would be a testimony to infinite human stupidity.

(Originally published on South China Morning Post on May. 26, 2022.)