Senior Colonel Zhou Bo (ret) is a senior fellow of the Centre for International Security and Strategy at Tsinghua University and a China Forum expert.

The swift and decisive response by countries of the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) to the riots in Kazakhstan raises a question for its peer in the region, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO): can it become equally effective in a similar situation?

Since the inauguration of the SCO in 2001, member states have held joint counterterrorism exercises almost annually, in line with the spirit of the group’s charter. But which country might really ask for cross-border help from the organisation?

The answer is probably none. Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, all member states of the SCO, are also allies in the CSTO. If necessary, they would seek help from the alliance first, as Kazakhstan proved recently.

China, India and Pakistan, meanwhile, are strong enough to deal with any domestic unrest without external help. The only uncertainty among SCO states is Uzbekistan, which left the CSTO in 2012.

The country in the region that needs most external help in counterterrorism efforts is Afghanistan, currently an observer state of the SCO. Cynically speaking, the heft of Afghanistan seems to lie in the troubles it might bring to other countries.

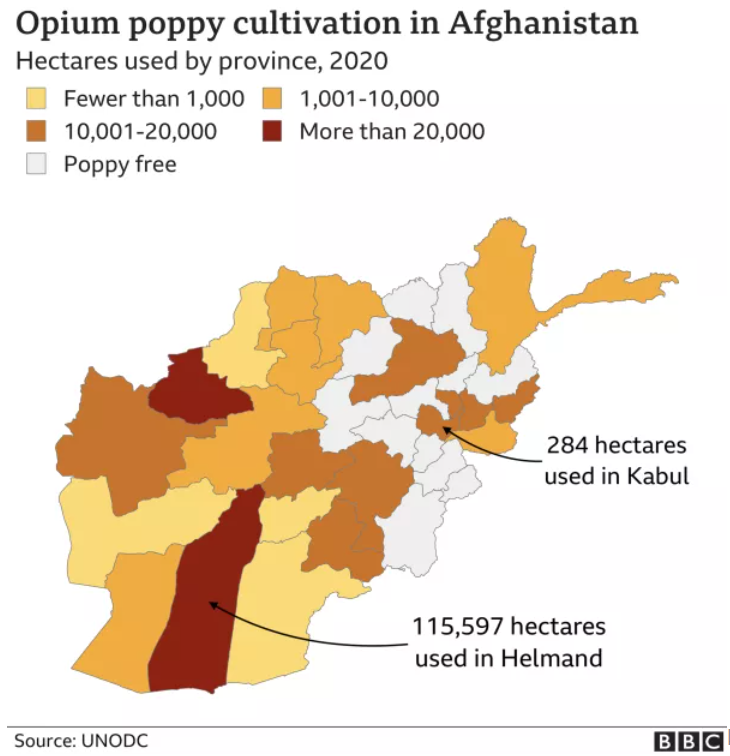

At the founding ceremony of the SCO, president Nursultan Nazarbayev of Kazakhstan described Afghanistan as “the cradle of terrorism, separatism and extremism” in his opening remarks. According to the UN, Afghanistan accounted for some 85 per cent of global opium production in 2020.

The wish of the international community is for the Taliban-led Afghan government to become moderate, inclusive and resolute in fighting terrorism. There is no guarantee of that, but at least the Taliban has said the right things, promising that people’s lives and property would be safeguarded and women’s rights respected.

Presumably, the leaders of this government have learned some lessons from their avatars who were in power before September 11.

The international community should therefore give the Taliban a chance to honour its promise, not least because the Afghan people are suffering from the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, exacerbated by the harsh winter, drought and insufficient international aid. More than half the country’s 40 million residents are reportedly facing food insecurity.

How can the SCO help? First and foremost, as de facto leaders of the SCO and permanent members of the UN Security Council, China and Russia should urge the US to lift its unilateral sanctions and unfreeze the more than US$9 billion in overseas central bank reserves as soon as possible. So far, the Biden administration has offered aid without dealing directly with the Taliban-led government it abhors.

This won’t work. According to The New York Times, aid groups have warned that 1 million Afghan children could die this winter. This may be alarmist, but even if 10,000 children die, it will be a crime rather than a shame. If Afghan people are dying while their money is in your hands, people can safely argue they are dying because of you.

Concurrently, the UN should lay down clear conditions that the Taliban has to meet in exchange for lifting sanctions. The Afghan people did not choose the Taliban, who took power by force, but there is no political party in sight that looks capable of replacing them any time soon. The challenge for the UN, then, is how to define such slippery words as “moderate” and “inclusive”.

If these terms mean including people who are not male or Pashtun in government, allowing women to work and girls to go to school, the Taliban would most probably agree since this is what they have already promised. At least on paper, these conditions are much easier to meet than those found in the Iranian or North Korean nuclear deals.

Although the SCO doesn’t necessarily need to recognise the legitimacy of the Taliban-led government now, it should use the SCO-Afghanistan Contact Group that was established in 2005 to liaise with the Taliban. Crucially, the Taliban must break away from all terrorist groups, even if they are bound by historical friendship, ideological similarity and even intermarriage.

Looking beyond the horizon, Afghanistan needs to become an SCO member state if it is to avoid looking like an enclave that leads to nowhere. The question is when. Afghanistan applied for full membership in 2015 and has been waiting ever since.

Can Kabul only join when it is no longer a problem? Or should the SCO let it in and resolve the problem from within? Or, if the problem is one which, like the pandemic, simply won’t go away, could the organisation learn to live with it?

In 2017, India and Pakistan both joined the SCO. Although the countries brought with them a seemingly irreconcilable mutual distrust, at least India’s economy, now the sixth largest in the world, has added strength to the organisation.

The benefit of granting Kabul full membership is that the SCO could play a pivotal role in mitigating worst-case scenarios. As a full member, the Afghan government – no matter who is in power – would be obliged to prevent extremist movements from spilling over into neighbouring countries.

Membership would also allow Afghanistan to be woven into the political and economic fabric of the region, something which is crucial for its future prosperity. After all, more than 60 per cent of Afghanistan’s trade is with SCO countries.

Afghanistan is not only landlocked, but it is almost SCO-locked as well. If it is not stable, the SCO will suffer. Striding over the Eurasian heartland is already a large undertaking. But for the SCO to become stronger, it should be brave enough to embrace a country that holds the key to regional peace and stability.

(Originally published on South China Morning Post on Feb. 4, 2022.)