Zhou Bo: Senior fellow at the Centre for International Security and Strategy, Tsinghua University and a China Forum expert

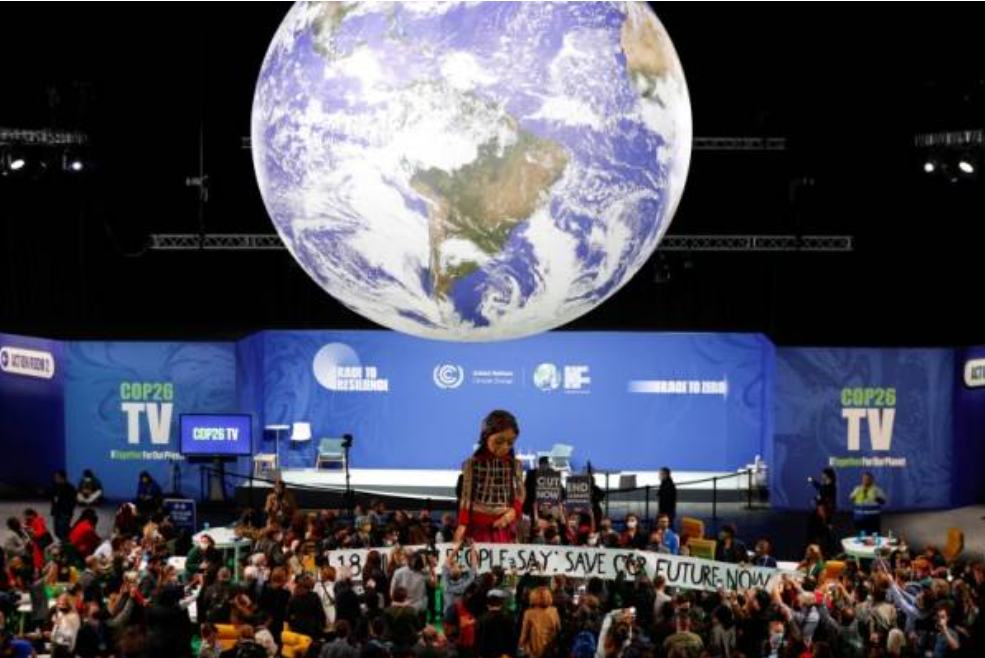

The joint pledge of China and the United States at the COP26 conference in Glasgow to cut emissions is like an oasis in a desert, considering their badly strained ties. But it shouldn’t be a surprise. In facing a common threat looming large over their own survival, major powers know when they need to act together.

The problem of climate change raises a question: if indeed time is running out – the most important consensus of the conference – do we still have time to compete against each other?

If human nature is intrinsically flawed so that people will only stop jostling each other right before doomsday, then climate change provides us with a way of looking at our relations from a perspective of coexistence: we cooperate to survive, we don’t survive to compete.

Coexistence is not easy, especially between two giants of almost equal weight. During the Cold War, strategic equilibrium between the two superpowers was eventually achieved through the doctrine of mutually assured destruction.

Admittedly, what is happening today is quite different from the Cold War if one thinks of the colossal amount of economic and other interdependence between China and the US. But, almost like in the early days of the Cold War, what we are seeing is ever intensifying competition to the extent that US President Joe Biden suggested to Chinese President Xi Jinping that they “establish a commonsense guardrail” in a virtual summit on November 16.

The question is how. Both China and the US have vowed not to slide into a new Cold War. But there is no guarantee of that.

Presumably, coexistence with the US is easier for China, not only because China’s time-honoured foreign policy is called “five principles of peaceful coexistence”, but also because – apart from what China views as its sovereign rights over Taiwan, and in the East China Sea and the South China Sea, that it has to defend – there is no possibility of a military conflict between China and the US elsewhere.

Against this bigger backdrop, Beijing does not wish to challenge the international system from which it has benefited tremendously for decades.

Coexistence with Beijing looks more like a bitter fruit for Washington to swallow, given that the US views the relationship very much like a duel between democracy and autocracy.

Ever since the establishment of diplomatic ties between the US and China, it has not been uncommon for American presidents to say how the US wishes for China to be strong and prosperous, but there has been an undertone, which was eventually voiced by US vice-president Mike Pence at the Hudson Institute in 2018: “After the fall of the Soviet Union, we assumed that a free China was inevitable”.

This hope has been dashed. China is getting much stronger, but is still different. During the Trump administration, the US took drastic measures to attack China, ranging from the trade war to increased US navy operations in Chinese waters in the South China Sea and lifting almost all legal restrictions on exchanges with Taiwan.

The Biden administration’s policy towards China is very much a continuation of Trump’s great power rivalry. But it seems things are starting to change.

In a recent interview with CNN’s Fareed Zakaria, US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said: “One of the errors of previous approaches to policy towards China has been a view that through US policy, we would bring about a fundamental transformation of the Chinese system. That is not the object of the Biden administration.” He even mentioned “coexistence”.

Even if the Biden-Xi summit signals a watershed, in a way, coexistence between Beijing and Washington today is more difficult than it was between Washington and Moscow during the Cold War. Unlike during the Cold War, when coexistence between two superpowers was marked by clearly defined spheres of influence, there aren’t even buffer zones between China and the US.

The US Navy regularly sends ships to sail through the Taiwan Strait and near the Chinese islands and rocks in the South China Sea while asking the Chinese People’s Liberation Army ships to keep a safe distance. Such brinkmanship risks veering into exactly what Biden hopes to avoid – a conflict, intended or unintended.

To stare into the abyss helps one to step back. Should a conflict occur, with the possible exception of Japan and Australia, no American ally would wish to take the US’ side. One can hardly imagine that Thailand, an American ally and a friend of China, would follow the US into a war with China under any circumstances.

If the US has succeeded in sweet-talking Australia into antagonising China, as was proved with the Aukus submarine deal, it has lost the trust of France, another important ally. The immediate outcome is zero, the long-term benefit is inconsequential.

The damage done by the Afghan war to the image and credibility of the US can only be matched by the Vietnam war. Some people have argued that America will rise from the ashes and prosper like it did 10 years after the Vietnam war. Perhaps it will. But even if that is so, there will still be the moment, maybe even before 2030, when China surpasses the US in terms of gross domestic product as the largest economy in the world.

I call it the “2030 moment”. It will be more epochal than the “Sputnik moment”, when the Soviets stunned the Americans by sending the first satellite to orbit, or what UN chief Antonio Guterres described as the “1945 moment” referring to the beginning of the Cold War.

For China, the “2030 moment” marks a return of history, a reconnection through a time tunnel with the heydays of the past. For America, it will be the first time that the country has to accept mutually assured coexistence with a rival since it became a global power after the war with Spain in 1898. And, for the whole world, it represents the comeback of common sense: nations rise and fall, the story of the rivalry between democracy and autocracy is a myth.

(This article was originally published on Nov. 24, South China Morning Post.)