Much has been said about the so-called Wolf Warrior diplomacy. Rhetoric aside, the real issue isChinese victimhood over the “century of humiliation” that started with the 1840 opium war.

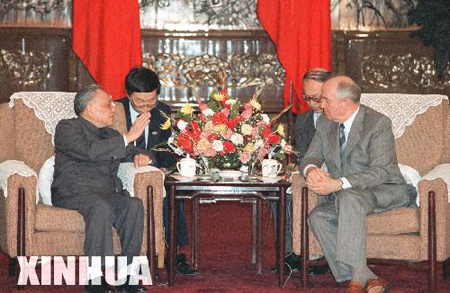

When Deng Xiaoping met Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in Beijing in 1989, he talked for quite some time about how China was maltreated by imperial Russia before he said “let’s put an end to the past and face the future”. In other words, he would not be able to talk about the future without first talking about the past.

China is not alone in succumbing to a sense of victimhood. I once saw a senior Finnish official become suddenly agitated because someone in the room mentioned “Finlandisation”. And victimhood can be a card. The best player is possibly Donald Trump, who once said: “Come to think of it, who gets attacked more than me?” As president-elect, he misled American voters into believing the strongest nation on earth was in “carnage” and that he could “Make America Great Again”. In the Oval Office, he lashed out at adversaries and allies alike as if the United States were a victim of the whole world.

A man’s acceptance of criticism also depends on his judgment of the critic’s intent. How many people really believe in claims of genocide in Xinjiang when the birth rate and lifespan of the Uygurs there have actually increased? This, rather than serious criticism, is demonisation.

In contrast, the US government did not declare the 1994 Rwandan war a genocide until it was practically over, out of concern that it would create an expectation that it would intervene.

When Mao Zedong declared that the Chinese people have “stood up” in 1949, the “century of humiliation” should have ended.

Even though it mostly occurred under Qing rule, it was such a short stretch that it failed even to overshadow the dynasty’s achievements. The High Qing era in particular saw sustained peace, economic prosperity, territorial expansion and population growth. The dynasty was essential to the subsequent formation of the concept of a Chinese nation.

Rather than a victim, China today is the envy of the world. The centre of international gravity is shifting towards East Asia. China is expected to surpass the US as the largest economy in the world in the 2030s or earlier.

Last year, Chinese consumers spent about US$6 trillion, a sum greater than the economy of Japan, a nation whose invasion last century still contributes to China’s sense of victimhood.

A few years ago, I heard what I thought was the most intriguing question at an international conference: if a rising China does not like American hegemony, then what would its ideal world order – one that the Chinese would love and foreigners would accept – look like?

There is no straight answer. Unlike Pax Britannica in the 19th century and Pax Americana in 20th century, the 21st century will not necessarily be Pax Sinica. Yes, China’s economic influence is felt worldwide. And in Africa and most of Southeast Asia, Beijing’s influence is greater than that of Washington.

But when China realises its goal of becoming a “strong, democratic, civilised, harmonious and modern socialist country” by 2049, the centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the US would still be the wealthier country when measured by gross domestic product per capita.

And a “world class” Chinese military is not necessarily stronger than the US military. It is more likely to be evenly matched.

So how can China contribute towards a better world?

First, unlike Washington, which wishes to bring its form of liberty to all, Beijing has no missionary zeal and prefers to help rather than police the world. Its caution in the use of force, as showed in China's peaceful rise in over four decades, would most certainly make the world a less volatile place. While the US military has been involved in one war after another, the People’s Liberation Army has restricted its military operations overseas to humanitarian aid.

Second, Beijing can share her experience in alleviating poverty with other developing countries, given that more than 700 million people are still living in extreme poverty worldwide. Who can be more qualified than China in this regard? In 2013, one in three counties in China, that is, 832 counties in total, was labelled as “poverty stricken”. Last November, China announced that they, too, had been lifted out of poverty.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative, too, will help to shape the world economic landscape for the better. Ironically, the initiative, which has been criticised for years by the West, now has a Western copycat. Build Back Better World, a new global infrastructure initiative by US President Joe Biden and the G7 partners, aims to narrow the funding gap of more than US$40 trillion needed in the developing world.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and especially when it comes from the most developed countries in the world. If this is what competition between China and the US looks like, the world will benefit.

What China will look like mid-century needs a bit of imagination. Presumably, it will retain some pleasant features of the Tang dynasty that the Chinese are most proud of, that is, diversity and tolerance.

Tang China was prosperous, multi-ethnic and cosmopolitan. It was home to ’foreign‘ religions ranging from Buddhism, Nestorianism, Zoroastrianism and Islam to Manichaeism. It set a good example of how a great power next to none can be confident and humble, loved rather than feared.

Senior Colonel Zhou Bo (ret) is a senior fellow at the Centre for International Security and Strategy at Tsinghua University and a China Forum expert

(Originally published on July 5, 2021, SCMP)