In fighting the novel coronavirus, China looks like anything but a developing country. It has reportedly provided all kinds of medical supplies to over 140 countries and international organisations and sent 14 medical expert teams to 12 countries. According to Cui Tiankai, the Chinese ambassador to the United States, by April 29, China had provided 14 masks for every American on average.

Since no one knows when the pandemic might end, such assistance is poised to continue. As a result, Beijing’s visibility will only rise.

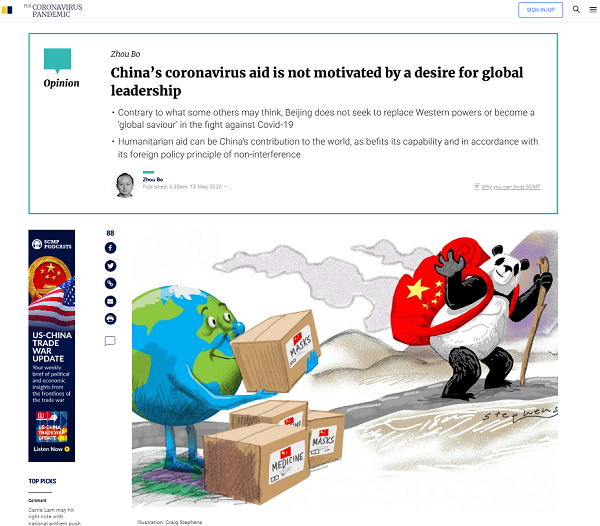

But make no mistake: this is not a sign of China wresting control of global leadership. Contrary to various allegations, China has not cast itself as a “global saviour” nor portrayed itself as an emerging superpower at a time that countries in the West are struggling to control domestic Covid-19 outbreaks. China has said it was only paying back the support it received when it was hit hard by the virus.

China does not harbour ambitions of global leadership in the first place. Its real ambition, as stated in its constitution, is to realise the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”. China has pledged a 30-year long march to achieve this by mid-century, with clearly defined goals at different stages.

The most telling example of its resolve is that even the pandemic has not dented the government’s commitment to eliminate extreme poverty by the end of this year.

Besides, Beijing’s influence is already ubiquitous. Today, it appears more comfortable than Washington with the international regimes and institutions that are designed by the West. While Americans have withdrawn from international treaties and institutions one after another, the Chinese have stepped in.

Chinese nationals now head four of the 15 specialised United Nations agencies that deal with economic activity, namely the Food and Agriculture Organisation, the International Telecommunications Union, the UN Industrial Development Organisation, and the International Civil Aviation Organisation.

The incorrect assumption about China’s “leadership” role has been made partly because of the natural instinct to look for leadership in a crisis. In 2008, major powers worked together to restore the global economy in the wake of the financial crisis, convening the inaugural G20 leaders’ summit for this purpose. Not this time.

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres fretted this month that there was a lack of leadership in the fight against Covid-19. Donald Trump appears to be the first American president who has neither the wish nor the ability to lead. Needless to say, his decision to halt funding for the World Health Organisation has sparked a global outcry.

The best way China can help the rest of the world is not to “lead”, but to provide public goods as a responsible power. The question is: how much can China provide? Citing its lower per capita GDP than that of developed nations and substantial regional differences in development, the Chinese government maintains that China is still a developing country.

But many in the West argue that the world’s second-largest economy, top manufacturer, holder of the world’s largest foreign exchange reserves and the biggest buyer of luxury goods cannot be a developing country. In 2019, China’s per capita GDP reached US$10,276, not that far from the US$12,376 of a “high-income economy” as defined by the World Bank.

There is a grain of truth in both statements. Whatever its status, the Chinese government has repeatedly said it would offer the world assistance in line with its actual strength. Indeed, its external aid has increased substantially in recent years.

In 2019, China overtook Japan to become the second-largest monetary contributor to the UN. After Trump withdrew US support for the WHO, China announced it would provide another US$30 million to fund the agency’s Covid-19 work, on top of the US$20 million it gave earlier.

The best public goods China can provide is humanitarian aid. Such support is the least controversial and, more importantly, almost tailor-made for China, whose foreign policy is anchored on non-interference. China has no appetite to replace the US as the “world’s cop” nor displace it in the Indo-Pacific region.

Notably, Chinese military operations overseas have been invariably humanitarian in nature, be it peacekeeping, counter-piracy or disaster relief. The PLA Navy’s hospital ship Ark Peace, for example, has provided medical services to over 230,000 people in 43 countries and regions in its 10 years of service.

And China is in a good position to provide humanitarian assistance. As the “world’s factory”, its industrial manufacturing capability is next to none. Before the coronavirus outbreak, very few Chinese – including me – realised how heavily the world depends on China for most basic medical supplies such as protective masks.

One can imagine that rich countries will do their utmost to improve their readiness for another virus attack, but what about poor nations? The need is massive. As The New York Times puts it, South Sudan has five vice-presidents and four ventilators, and 10 African countries have no ventilators at all.

The rising global death toll reminds us that an invisible pathogen can be far more lethal than a financial crisis or major power competition. It pushes us to rethink what is most important in life, not only for oneself, but also for families and societies.

This pandemic won’t be the last. If China’s assistance signals how it could again step in, come the next disaster, it is the best news for the world at the worst time.

The article was first published on the South China Morning Post on 13th, May